It has been a while since our last blog but here we are again! We recently gave a tutorial about SeaHorn as part of the Automated Formal Methods Workshop (AFM) and the Seventh Summer School on Formal Techniques (SSSFT) that took place on May 20th at Menlo College, Atherton (CA). In this post, we reproduce the most interesting parts of the tutorial.

In the first part of the tutorial, we described the basic usage of SeaHorn as well as how it can be combined with two interesting tools: crab-llvm, an abstract interpreter for LLVM programs, and sally, a model checker for infinite transition systems. In the second part, we shown a case study on how to prove memory safety using SeaHorn.

We started our tutorial with this simple C program test.true.c:

#include "seahorn/seahorn.h"

extern int nd(void);

int main(void) {

int n, k, j;

n = nd();

assume (n>0);

k = nd();

assume (k>n);

j = 0;

#pragma clang loop unroll(disable)

while( j < n ) {

j++;

k--;

}

sassert(k>=0);

return 0;

}The program test.true.c is standard C except there are two special

annotations, both defined in the header file seahorn.h which is part

of the SeaHorn distribution. The annotation assume(cond), where

cond can be any C expression that evaluates to a Boolean, can be

used to either add extra assumptions about the environment or guide

SeaHorn during its search for inductive invariants. The annotation

sassert(cond) is equivalent to C assert. The reason why we use

sassert rather than assert is that sassert is actually defined

as

# define sassert(X) if(!(X)) __VERIFIER_error ()This definition allows SeaHorn to reduce the validation of an

assertion to the problem of deciding whether the error state denoted

by __VERIFIER_error is reachable or not.

Note that there is also in the program an external function nd. In

SeaHorn any external function (denoted with C keyword extern) that

returns a value of type ty is modeled as a function that returns

non-deterministically a value of type ty. This simple mechanism

allows SeaHorn to have code abstractions. Note that the external

function does not need to be named nd. Any external function that

returns an integer will make the trick here.

Let us continue now by running SeaHorn on the program. The first thing that SeaHorn can do is to translate the C program into LLVM bitcode:

sea fe test.true.c -o test.true.bcThe option fe (front-end) calls clang to translate C into bitcode

and performs some preprocessing and optimization of the bitcode. You

can see the content of test.true.bc by translating it into

human-readable bitcode format:

llvm-dis test.true.bc -o test.true.llA better option is to use the SeaHorn utility inspect as follows:

sea inspect --cfg-dot test.true.bc

dot -Tpng main.dot -o main.dot.png

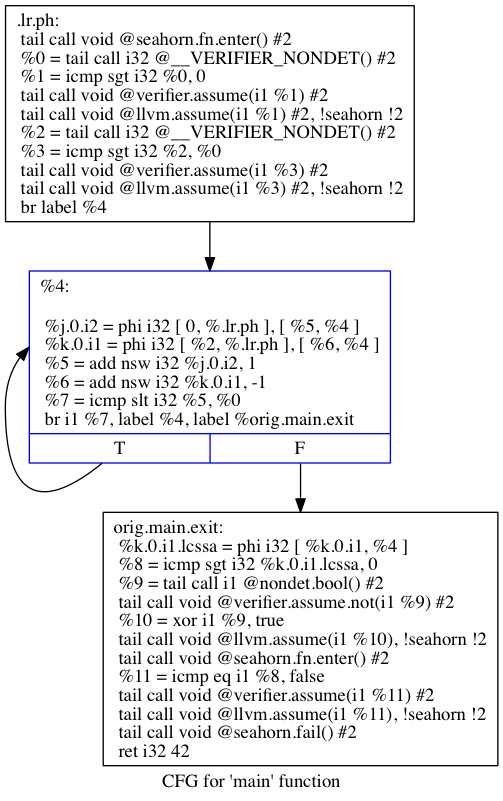

open main.dot.png // on Linux replace `open` with your favorite `png` viewerThis command sequence converts first the bitcode to .dot format and

then to a png file. If you open the png file then you should see

something like this:

Next, we can use SeaHorn to translate the LLVM bitcode into verification conditions. We use Horn Clauses as the language to represent verification conditions.

sea horn test.true.bc --step=small -o test.true.smtThe option horn outputs the verification conditions in

test.true.smt. By default, this option uses a format that resembles

SMT-lib:

;;; declare relations: one per basic block

(declare-rel main@.lr.ph ())

(declare-rel main@_bb (Int Int Int ))

(declare-rel main@orig.main.exit (Int ))

(declare-rel main@orig.main.exit.split ())

;;; declare variables

(declare-var main@%_8_0 Bool )

(declare-var main@%_9_0 Bool )

(declare-var main@%_10_0 Bool )

(declare-var main@%_11_0 Bool )

(declare-var main@%_7_0 Bool )

(declare-var main@%_1_0 Bool )

(declare-var main@%_3_0 Bool )

(declare-var main@%_0_0 Int )

(declare-var main@%_2_0 Int )

(declare-var main@%j.0.i2_0 Int )

(declare-var main@%k.0.i1_0 Int )

(declare-var main@%_5_0 Int )

(declare-var main@%_6_0 Int )

(declare-var main@%j.0.i2_1 Int )

(declare-var main@%k.0.i1_1 Int )

(declare-var main@%k.0.i1.lcssa_0 Int )

;;; definition of the Horn clauses that have this form

;;; (rule (=> (and p .... ) p'))

;;; such that there is an edge from p to p' in the CFG of the program

(rule main@.lr.ph) ; entry block is always reachable

(rule (=> (and main@.lr.ph

true

(= main@%_1_0 (> main@%_0_0 0))

main@%_1_0

(= main@%_3_0 (> main@%_2_0 main@%_0_0))

main@%_3_0

(= main@%j.0.i2_0 0)

(= main@%k.0.i1_0 main@%_2_0))

(main@_bb main@%j.0.i2_0 main@%k.0.i1_0 main@%_0_0)))

(rule (=> (and (main@_bb main@%j.0.i2_0 main@%k.0.i1_0 main@%_0_0)

true

(= main@%_5_0 (+ main@%j.0.i2_0 1))

(= main@%_6_0 (+ main@%k.0.i1_0 (- 1)))

(= main@%_7_0 (< main@%_5_0 main@%_0_0))

main@%_7_0

(= main@%j.0.i2_1 main@%_5_0)

(= main@%k.0.i1_1 main@%_6_0))

(main@_bb main@%j.0.i2_1 main@%k.0.i1_1 main@%_0_0)))

(rule (=> (and (main@_bb main@%j.0.i2_0 main@%k.0.i1_0 main@%_0_0)

true

(= main@%_5_0 (+ main@%j.0.i2_0 1))

(= main@%_6_0 (+ main@%k.0.i1_0 (- 1)))

(= main@%_7_0 (< main@%_5_0 main@%_0_0))

(not main@%_7_0)

(= main@%k.0.i1.lcssa_0 main@%k.0.i1_0))

(main@orig.main.exit main@%k.0.i1.lcssa_0)))

(rule (=> (and (main@orig.main.exit main@%k.0.i1.lcssa_0)

true

(= main@%_8_0 (> main@%k.0.i1.lcssa_0 0))

(not main@%_9_0)

(= main@%_10_0 (xor main@%_9_0 true))

(= main@%_11_0 (= main@%_8_0 false))

main@%_11_0)

main@orig.main.exit.split))

;;; query

(query main@orig.main.exit.split)Once we have generated the verification conditions we can use SeaHorn

back-end solvers to try to solve them by adding the option --solve:

sea horn --solve test.true.bc --step=small --show-invarsThe default solver used in SeaHorn

is Spacer which is a PDR-based

(PDR refers to Property-Directed Reachability, aka IC3) solver built

on the top of Z3. spacer infers

inductive invariants over linear integer/real arithmetic and

quantified-free arrays from recursive, non-linear Horn

clauses. spacer also computes summaries in presence of

functions. These are the invariants inferred by spacer:

unsat

Function: main

main@.lr.ph: true

main@_bb:

([+

-1*main@%j.0.i2

-1*main@%k.0.i1

main@%_0

]<=-1)

(main@%k.0.i1>=2)

main@orig.main.exit: (main@%k.0.i1.lcssa>=2)

main@orig.main.exit.split: falseSeaHorn shows first that the query is unsat meaning that the error

location (denoted by __VERIFIER_error) cannot be reachable, and

therefore the program is safe!. In addition, SeaHorn outputs for each

basic block the inferred invariants. For instance, for the basic block

_bb at main (the loop) the invariant is the formula %j.0.i2 +

%k.0.i1 >= %_0 + 1. With a bit of faith, you can convince yourself

that %j.0.i2, %k.0.i1, and %_0 correspond to the C variables

j, k, and n.

For convenience, SeaHorn allows to write all the above commands in a single command:

sea pf test.true.c --step=small --show-invarsNow, lets see a buggy version called test.false.c:

#include "seahorn/seahorn.h"

extern int nd(void);

int main(void) {

int n, k, j;

n = nd();

k = nd();

assume(k >= 2);

j = 0;

#pragma clang loop unroll(disable)

while( j < n ) {

j++;

k--;

}

sassert(k>=0);

return 0;

}Let us try to prove that it is safe:

sea pf test.false.c --show-invarsSeaHorn outputs the following:

sat

main@.lr.ph

main@.lr.ph --> main@.lr.ph

main@.lr.ph --> main@.lr.ph

main@.lr.ph --> main@orig.main.exit.split

main@orig.main.exit.split --> query!1Here, the solver outputs sat meaning that the error location is

reachable and therefore the program is unsafe. In addition, it outputs

the relations that were reachable during the unsafe trace found by the

solver. Although this can be helpful to understand why the program is

unsafe, it cannot be considered a valid counterexample.

We already describe in a previous post how to generate automatically executable test harnesses for failed properties. Let us execute these two commands:

sea pf test.false.c --cex=harness.ll

sea exe -m64 -g test.false.c harness.ll -o outThe above commands produce an executable out which can be executed

by simply typing:

./outYou should see a printed message that indicates __VERIFIER_error was

reached:

__VERIFIER_error was executedThis shows that the error location is indeed reachable and therefore the counterexample found by the solve is an actual counterexample. More importantly, a key advantage of having an executable is that we can run now our favorite debugger and inspect why the program failed:

lldb ./out

(lldb) b main

(lldb) run

14 int main(void) {

15 int n, k, j;

-> 16 n = nd();

17 k = nd();

18 assume(k >= 2);

19 j = 0;

(lldb) n

14 int main(void) {

15 int n, k, j;

16 n = nd();

-> 17 k = nd();

18 assume(k >= 2);

19 j = 0;

20 while( j < n ) {

(lldb) n

15 int n, k, j;

16 n = nd();

17 k = nd();

-> 18 assume(k >= 2);

19 j = 0;

20 while( j < n ) {

21 j++;

(lldb) p n

(int) $0 = 3 // the value of n

(lldb) p k

(int) $1 = 2 // the value of k

(lldb) p n // several times until the exit of the loop is taken

21 j++;

22 k--;

23 }

-> 24 sassert(k>=0);

25 return 0;

26 }

(lldb) p k

(int) $2 = -1

(lldb) n

__VERIFIER_error was executedThe reason for failure was that n and k can be set initially to

3 and 2. Then, the program executes the loop three times and when

the exit of the loop is taken the value of k is -1.